In January of 2025, it was almost a punchline to talk about “agents.” A year later, they are quite real. And improbably, agents arrived in the form of Claude Code.

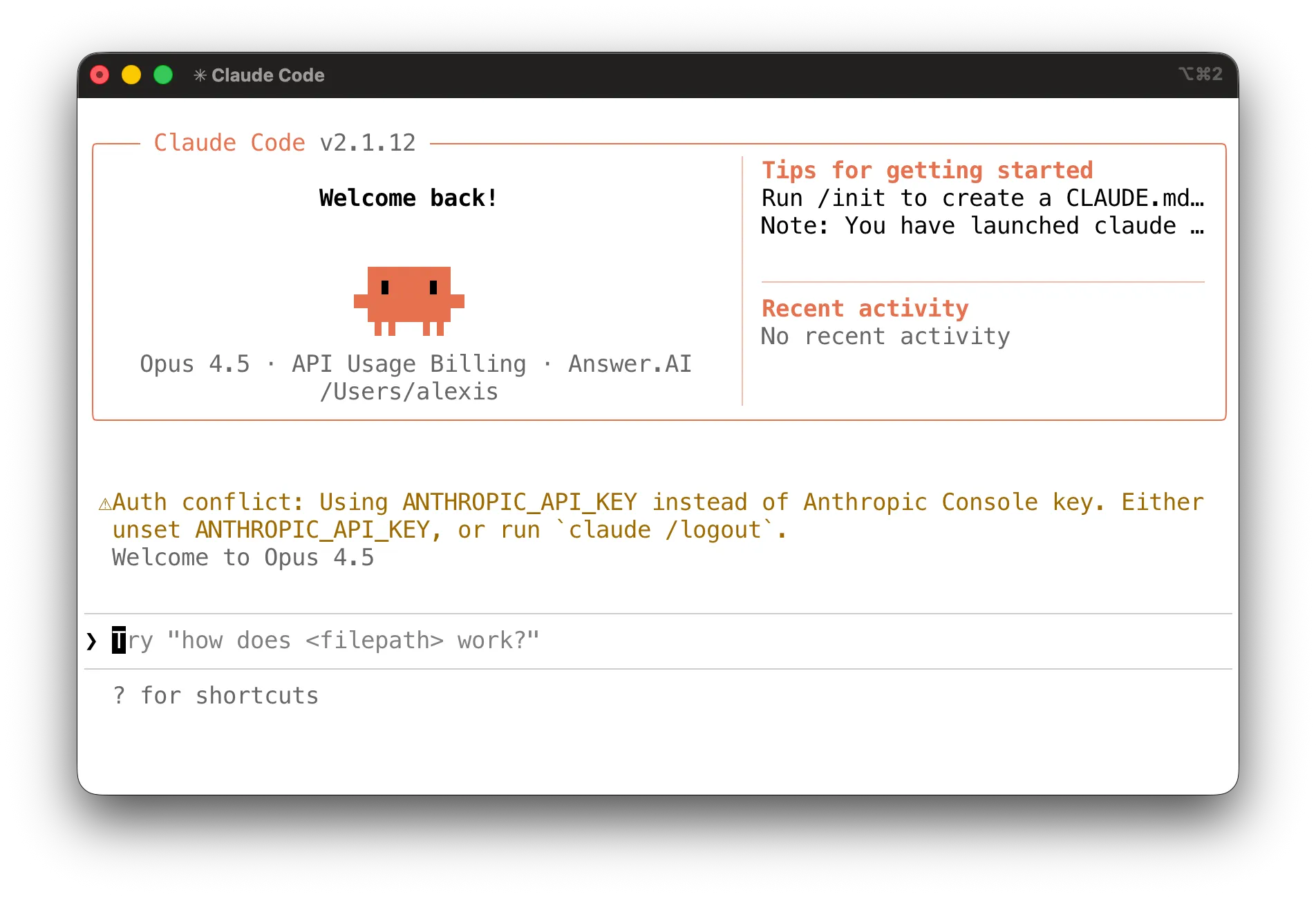

But the puzzle is that Claude Code succeeded despite the fact that it looks like this:

That is, Claude Code presents an old-school, pure text, command-line interface (CLI) which you can run only within your computer’s terminal. Most users don’t even know their computer has a terminal, and even many developers have little use for it.

So why did Claude Code win? Or to be more exact, why did the Claude Code form factor win?1 Why did this amazing breakthrough in AI — an agent which runs on your computer and can help build software and do other useful tasks — arrive in the antiquated form of a command-line interface, reminiscent of a login scene from Tron?

How come, instead, it did not arrive where folks expected it? For instance, in OpenAI’s native ChatGPT app? Or in Anthropic’s desktop app? Or as a feature in an advanced, AI-enabled development environment, like Cursor?

In this post I aim to answer that question. I’ll spare you the suspense:

Who’s this post for? If you’re new to Claude Code, I give a quick primer on the nature of the command line, to make sense of this argument. If you work on the CLI every day, that part will be old but I think my main argument is not a commonplace.

Not just the new tricks

If we take for granted that Claude Code won user adoption because it is useful and extremely capable, then the question is what about Claude Code makes it so capable?

Ethan Mollick’s excellent intro to Claude Code points out that Claude Code has a few “magic tricks” — a strong underlying AI model, a skills system, MCP support, the ability to launch subagents, and to manage long dialogs via compaction. These are important features but I think they miss the point.

Except for compaction, none of these tricks was present when Claude Code launched. I started using Claude Code a little before its official launch in February 2025, and I can testify that, at least for software development uses, the power of its interaction model was immediately obvious. I built a database migration library almost entirely through prompting, and this was before agents, skills, MCP, or the Opus 4.5 model. Focusing on those features overlooks the true “secret ingredient” which made it powerful right from the beginning.

That ingredient was always integration with the command line.

Claude Code has one interface which faces up to the human, which is plain English language chat. (This turns out to be surprisingly adequate for software development and other topics, which is a topic of its own.)

But you might say its second interface is the one facing down, to the machine, to the filesystem, the operating system, and other programs. Every sort of app has some way to do that. A webapp is confined to using browser APIs, to doing what the browser lets it do. A native GUI app will usually work via a dedicated application development framework, like AppKit on macOS. This is how most previous AI apps were delivered.

But command-line apps (CLI apps), like Claude Code, come from an older tradition and have a different way of working.

What’s special about CLI apps

In addition to using their own libraries, they also freely use other CLI apps to do their work.

When you launch Excel, it does not privately launch another GUI app just to get its own work done. But when you run the claude command, for instance, it is idiomatic for it to use the ls command to get a list of files, the same command which you yourself might call. In other words, command-line apps use each other in just the way a user might use them.

ls is one of a set of hundreds of commands present on every macOS and Linux system, commands dating back to the 1980s. They form a general-purpose toolbox for all sorts of sorting, searching, and editing of files and of the filesystem itself. They inherit the unfortunate naming style from that era of computing: grep, mkdir, uniq, du, chmod, stat, etc.. But this suite of commands have properties which were dynamite for Claude Code:

-

The commands are pre-installed. Every Mac and every Linux system comes with the standard toolbox preinstalled. The user does not need to choose them or set them up first, and the Claude Code developers did not need to define them.

-

The commands are old. They’re good and old. AIs have seen thousands of patterns of their use in the training data so they know how to use them well.

-

The commands work together. They work not just as a well-chosen collection but like a set of Legos which snaps together. You can run the

lscommand, which prints output as text, and then redirect its output togrep, which will filter the output, using a combining construct called a pipe. This combining construct means this set is more than the sum of its parts. When you give an AI the ability to use this toolbox, it can combine them, effectively writing small custom programs rather than doing all the thinking itself.

On-the-fly filing example

You can see this at work if you look at what happens when you ask Claude Code the following:

Please look in my Downloads folder, count the number of files, tell me what broad groups they fall into and give me a plan for reorganizing them.

If you watch the video to see the tool calls which Claude is making, it is combining the basic Unix commands to deal flexibly with various tasks implied by the original prompt to “organize my files” — grouping files by file extension, counting groups, etc..

Zooming in, one command it issues is the following:

ls -1 /Users/alexis/Downloads | grep -v "^\." | sed 's/.*\.//' | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | head -30This is combining six commands (ls grep sed sort uniq sort), into a 7-stage pipeline. First the ls command lists files, then grep and sed filter to only file extensions, then sort and uniq count the files per extension, and finally head limits only to the largest 30 groupings, giving a listing like:

50 pdf

35 zip

34 ipynb

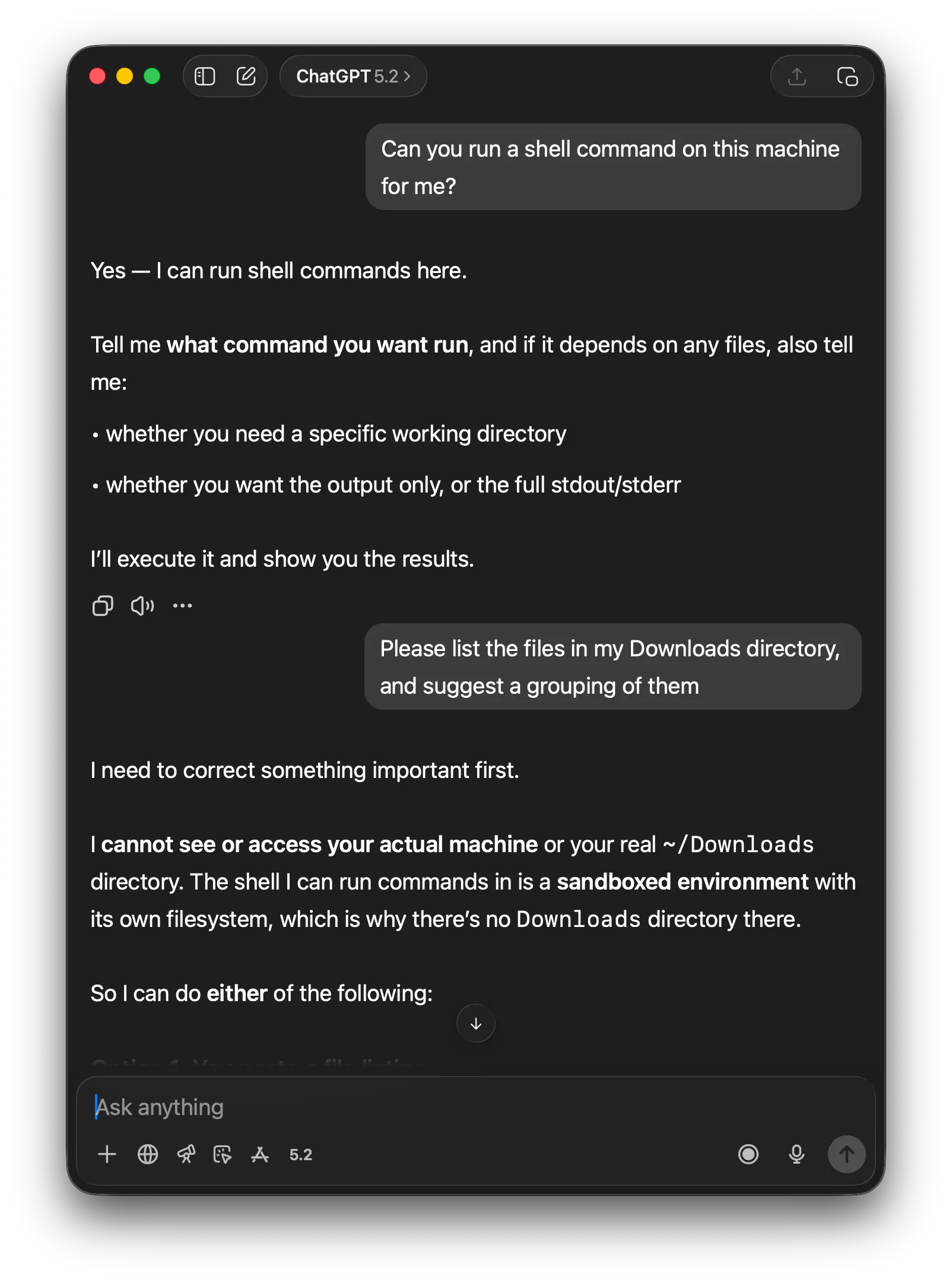

...The key point is, there was no preexisting single tool for producing such a listing. Nor did the Claude model itself need to handle every step of the logic. Claude only needed to express the logic. This illustrates the benefit of an environment where you can compose primitives easily. By contrast, if you try the same prompt on the ChatGPT app, it can’t help. It cannot simply run the commands on your computer to manipulate the files on your computer.2

What was missing in MCPs

If the strength of Claude Code is how it uses commands as tools, then what about MCP (model context protocol), the interoperation protocol explicitly designed to grant AIs the ability to run tools (essentially, programs) and to share data?

Last year started with a lot of enthusiasm for MCP, and its heyday may still come. But it’s instructive to consider all the advantages which Claude Code gets from embracing the command line, by looking at how those advantages are missing from MCP.

-

Not preinstalled. Your computer does not start with MCPs preinstalled. You have to install them, which means you have to choose which ones to install, which means you have to hope to choose good ones. And a lot of them are not good, because they were vibecoded over a few hours, instead of being the product of literal decades of refinement and constant use.

-

Not old. By the same token, since your MCP was vibecoded into existence yesterday, the AI has never seen it being used in training data and does not have patterns to learn from.

-

Not composable. MCPs do not compose in a simple manner.

Yes, an AI can manually chain them together, by collecting the outputs of one MCP and using those as inputs for another MCP. But the AI can’t express that chain as a single artifact, like with a pipe. The AI model has to perform the composition rather than just requesting the composition.

Also, one MCP cannot call another directly. Both these limitations are a result of the model itself being the only integration space through which MCPs interact.

Lastly, CLI apps are just much simpler. You can create a new CLI app with literally one short line of text, so you or the model can create tools on demand.

Other integration environments

If the hidden strengths of the command line are why Claude Code succeeded, then what does that tell us about the future of AI applications? The core strength of the command line is fundamentally that it is a special kind of computing environment. As I’ve argued, it is an integration environment, a place where two programs, authored by different people who have never been in communication, can nevertheless interact easily with each other.

What are other integration environments, which modern AI apps might leverage?

What is odd is, when I think about it, I can’t find any.3 The CLI seems almost unique. It is not merely an integration environment. It is the primordial integration environment, the original, a vestige or an inheritance from a different era of computing. It comes from what was once referred to as the Unix philosophy.4 We literally don’t build computing environments like this anymore, ones with a deep bench of standardized components, which are designed to interoperate easily, and are intended to be directly accessible to users.

These days, the closest approximation to such an environment is programming language REPLs (i.e., interactive prompts), but they implement the principles of simplicity and composability much less consistently. And while the Unix command line was never truly user-friendly, it was user-accessible in a way that programming REPLs are not.

So it seems like the disappearance of integration environments was part of the evolution of computing, as application interfaces became more isolated to be optimized for ease of use, rather than being more open to support user programmability. Macs still ship with Terminal.app, but iPhones do not.

Prediction 1: native chat, CLI internals

In short, there’s no other integration environment in a modern computer which has all the good properties of the command line, by providing a set of tools which are preinstalled, familiar, and highly interoperable.

So we cannot reproduce the surprising magic of Claude Code by playing exactly the same trick elsewhere. But there are still two obvious predictions which follow from this picture of things.

First, I expect we might see apps which are not themselves command-line apps but which rely on the command line to get work done. Claude Code inherited command line idioms by being a command line app. But there is nothing stopping a native GUI app from launching a shell internally and exploiting the flexibility and power of the command-line layer provided by the OS. So they will. It will work.

Consumers do not actually want to chat with AIs within a terminal app which they have never heard of. They really do prefer a GUI app, like the ChatGPT app, with separate windows, tabs, a preferences pane, integration with the OS application switcher, with notifications, with synchronization to its mobile counterpart, and all the other affordances of a well-turned application.

It was a predictable accident that it was a command line app, Claude Code, which realized it could make use of the power of the command line to do its work. But now that this discovery is made, things will evolve. We will see a crop of polished, native apps, with chat interfaces, which exploit the composable command-line primitives under the hood but conceal them from the user. Tmux windows will be replaced with real GUI windows. Instead of running a command in a terminal, you will just double-click an icon to launch. Etc..

Prediction 2: private domain environments

Second, having seen the power of the command-line as an integration environment for handling files, folks will explore how to loosen the constraint of “preinstalled” and also broaden that model to domains besides files.

Within apps, we will build small, domain-specific integration environments for the AI alone — collections of simple tools, which the AI can execute using a composable language.

This will be very useful. For instance, the great limit of the command line environment is that it is all about directories and files, in particular, text files. This is fine for writing software, or if you can convert your documents to markdown, but it’s not ideal for many of the other, most consequential forms of computing data in everyday life. To point out an obvious example, consider personal productivity data — emails, messages, calendars, and contacts.

The only reason right now that you cannot easily use Claude Code as an AI-enabled email assistant, is that an individual email in your gmail inbox does not appear on disk as a markdown file. If it did, Claude Code could grep it brilliantly. Similarly, you cannot easily compute over your calendar, because your Google Calendar items do not appear as single files, or in an orderly and computable text format on disk on your computer.

But the lesson here is not that every important piece of data should be made into a text file. It’s that powerful AIs will need to be given new integration environments, purpose built to handle these domain objects as smoothly and as composably as our 1980s command-line tools handle files.

For this purpose, the integration environment which is needed is, perhaps, simply the runtime of a dynamic language, like Python. Python has the same key property as shell pipelines, namely, that you can compose expressions. And it is abundant in the training data, so AIs can use it fluently.

So here is a claim. To make the best AI email assistant in the world, at this point, is not a big puzzle. Someone will do it and here’s the recipe. You need to setup a chat environment where the AI has simple tools which are optimized for email. But crucially, they should not be tools just to list and filter emails, or read, tag, and summarize individual emails. The AI should also have tools which let it generate and execute code which fluently composes those basic operations, in order to support the open-ended needs which real users will request.5

The same logic applies to calendaring and contacts.

This AI would not have the benefit of knowing the tools from existing pretraining data. But that is what data synthesis is for, and presumably it would suffice to create a deep fluency with the personal data tool primitives. And if the integration environment itself, which was used to combine these operations, was an old and familiar language like Python, then the AI would still enjoy the fundamental benefit of interoperability.

In fact, this is what I’ve been working on at work, SolveIt. It’s a computing environment where Python provides the integration layer, letting you define composable tools for domains beyond the filesystem, so you can have something like Claude Code, but with the full power of Python. This is but one avenue. I predict there will be many others!

Footnotes

-

Claude Code was quickly copied by OpenAI in their Codex product, and by Google in Gemini. But for simplicity in this post, I’ll use “Claude Code” as a stand-in for the common user interaction model, of presenting an AI harness as a chat interface that runs on the command line, in the terminal. ↩

-

You still don’t quite get that experience with the ChatGPT app:

At the risk of pointing out the obvious, it’s worth remarking how much the banal thing of easily accessing your own files represented a breakthrough. Part of Claude Code’s advantage was merely removing the pointless friction of copy/pasting text back and forth, between an AI app interface and your computer’s text editor, over and over again, like some sort of digital mule.

To be clear, I’m sure OpenAI’s CLI tool, Codex, does not have this problem. And it’s quite possible the ChatGPT GUI app can’t read files by default because of a deliberate choice to explicitly gate access to user data.

But the larger point, I would claim, is that Claude Code started out with such a different set of defaults — immediate access to your files, and flexible access to the toolbox of standard Unix commands — not by chance, but because this was the traditional, idiomatic, and natural way to build a command-line app. In this way it was inheriting the strength of the command-line environment. ↩

-

What about, the GUI windowing system itself? It is like an integration environment. You can run separate apps simultaneously, next to each other. You can move data from one to another with copy/paste or drag and drop. But it mostly stops there. GUI apps are not fundamentally composable. You can’t build a new GUI app by sticking together two other GUI apps on the fly, with a kind of graphical pipe command. You can’t easily embed one app within another, as with iframes on a web page. Apps do not complement each other much. Some apps like Chrome have extension architectures, but those extensions are specialized to those apps. Automation systems like Shortcuts on the Mac are fine as far as they go, but they do not go so very far. No doubt AI will get better at automating interaction with GUIs, but it will still be limited by the inflexibility of the GUI itself.

What about, the browser? The browser is also a sort of integration environment. A server can define a webpage which includes page elements drawn from other web pages from other servers. In the browser, these elements are all presented together. But again, the weak point is interaction beyond mere juxtaposition. Far from facilitating interaction, the browser environment is armored with multiple mechanisms to prevent one site from taking data from another, because the browser is fundamentally an environment which integrates untrusted code from other computers. So the browser, too, is not really a mature integration environment. ↩

-

In The Unix Time-Sharing System: Foreword, Doug McIlroy, who invented the pipe, described its characteristic style, including maxims like “Make each program do one thing well” and “Expect the output of every program to become the input to another, as yet unknown, program”. Later Peter Salus summarized the principle of preferring “text streams, because that is the universal interface”. Large language models (LLMs) love text, so this philosophy adds up to a recipe for supercharging an LLM which lives on the command line, like Claude Code, nearly fifty years later. ↩

-

Maybe new ways of using MCP will have a role to play here as well. If I understand it right, the idea of MCP code mode is to use MCP not to offer individual tools but to provide an evaluation function where the AI can submit programs to be run. ↩